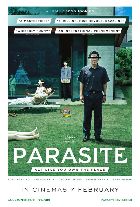

Parasite, the new movie from South Korean director Bong Joon-ho, has made history in more ways than one.

Not content with its historic Oscar wins for Best Picture, Best International Feature and Best Director, the movie has also set strong box office totals for a foreign language movie here in the UK. ScreenDaily reports it's the third-highest-grossing foreign-language release of all time in the UK, with its current tally of £5.1 million just lagging behind Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and The Passion of the Christ.

It's a remarkable success story, and a sign of how Parasite has broken out into the mainstream to get everyone talking. Bong's film is a perverse yet uproariously funny of the haves and have-nots, exploring what happens when a lower-class South Korean family infiltrates the lives of their wealthier compatriots – with disastrous results.

The movie's deft, unpredictable tapestry of broad comedy, trenchant social satire and bone-chilling horror is a trademark of the director. Those familiar with his previous movies, including the Chris Evans-starring dystopian sci-fi Snowpiercer, will be very familiar with these quicksilver changes in tone – like all of Bong's films, Parasite remains 10 steps ahead of the viewer at every turn.

For those who've seen the movie (and no doubt can't wait to see it again), here's our spoiler-filled deep dive into the ending. Not yet seen it? Then be sure to come back later on.

WARNING: PARASITE SPOILERS AHEAD

At the end of Bong's searing social critique, life for both the sub-strata Kim family and the affluent Park family has descended into chaos. The Kims' attempt to emulate the lives of the upper-classes backfire spectacularly when they unleash the machinations of another family, who have been living in the Parks' atomic bunker, unobserved and unmolested, for years.

Everything descends into a bloodbath when the rampaging Geun-sae (Park Myung-hoon), previously tied up in the bunker, escapes captivity to seek vengeance for the earlier death of his wife, the Parks' former housekeeper Gook Moon-gwang (Lee Jung-eun). She had been supplanted in favour of Kim Chung-sook (Jang Hye-jin), the social-climbing matriarch of a brood that encompasses father Kim Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho), son Kim Ki-woo (Choi Woo-shik) and daughter Kim Ki-jeong (Park So-dam).

That Geun-sae's eventual massacre takes place in the midst of a tastefully appointed birthday party for the Parks' young son Park Da-song (Jung Hyeon-jun) only accentuates the sense of horror and absurdity. In the aftermath, the Kims are compelled to return to their near-subterranean existence, albeit in the absence of their father, who, following the violence, has retreated into the bunker formerly occupied by Geun-sae.

This is as close as the Kims can get to crossing the social divide, Kim Ki-taek vicariously living the existence of those in the house above, while every night sneaking out to steal food from the fridge. The marvellously bleak ending implies that Kim Ki-woo has progressed in purchasing the former Park residence in order to give his family the lifestyle they deserve; the final shot, however, cranes down into the Kims' squalid residence to reveal that it's nothing more than a pipe-dream, a wish-fulfillment fantasy gone sour.

That very camera movement embodies the philosophy of Parasite. Throughout, we're witness to a delightfully fluid visual aesthetic that constantly cranes from high to low, between rich and poor, aspirational and affluent, underlining the class divides that streak throughout Korean society (and, by extension, the entire world).

Earlier in the movie, this is potently expressed in the flood sequence; the Parks can simply close their glass doors and watch the rain pattering on their elaborately manicured lawn. But the Kims have to beat a retreat back down into the heart of the city, descending step after step into a hellish existence where the streets are flooded, and their home ruined. Hong Kyung-po's cinematography literally and figuratively takes us from euphoria to despair, accentuating a social critique of which Charles Dickens would surely have been proud.

These divisions are, of course, emphasised in the brilliant production design, which contrasts the Kims' lowly residence, around which they have to scramble to receive free wi-fi, with the elaborately perched Park household, resplendent in space, glass and stylish furnishings. The house, like the characters, looks out, and down, on everyone else, but remains barred from easy access by a locked gate. The Parks are intrinsically connected to the very people on whom they step, by virtue of the fact they live in the same geographical space, but want nothing to do with them.

Yet the brilliance of Bong's direction and screenplay shows how these threads are interwoven like some kind of invisible gordian knot. In the film's first dip into horror territory, it's revealed that the Parks' deposed former housekeeper has been keeping her husband underground, affording him the fringe benefits of worry-free living while denying him the basic human pleasures of seeing the sky, or feeling the weather.

Despite the Parks' inordinate wealth, the balance of power appears to shift to the increasingly psychotic Geun-sae, who 'communicates' with the Kims' patriarch Park Dong-ik (Lee Sun-kyun) by headbutting the underground light switch as he walks up the stairs into his home. Park Dong-ik and his family mistakenly believe the lights to be motion-activated; in reality, we're presented with an underclass extending their tendrils into a hermetically-sealed, upper-class lifestyle without the Parks ever knowing about it. (At least until the end, where it all goes horribly south.)

This is a literal embodiment of the metaphorical class divide that streaks through the narrative. After all, the wealthy Parks are defined by those they've overtaken, in a social and economic sense; in order to ascend to a higher ladder, one must step over those less fortunate. Yet everyone is intrinsically tied to one another, whether they like it or not. This is the horrible inevitability that Bong appears to be driving at throughout the movie; we're tempted to direct the 'parasitic' label at either the Parks or the Kims, and although both broods do plenty to invite the analogy, they are all victims of a wider parasitic social mechanism, one that means different things to those on either side of the social divide.

The Kims, an expert family of con artists, are feverishly intent on living the rich life that has been so far denied them; this ideology works its way under their skin, occupying their entire behaviour and existence up to, and beyond, the moment where they've replaced all of the Parks' original employees. The Parks, on the other hand, are enjoying a comparatively worry-free existence, but in the process open themselves up as easy targets to the likes of the Kims.

Of course, at the same time, the Parks are indirectly, even parasitically, feeding off the likes of the Kims, not to mention Geun-sae and his wife, at all times, wanting for nothing and demanding everything when they want it. This becomes apparent immediately prior to the climactic birthday party massacre, where Park Dong-ik aggressively asserts his social status to the disgruntled Kim Ki-taek. That both men are wearing Native American uniforms, in-keeping with the theme of the party, is another example of the film's focus on identity fluidity, the idea of becoming pre-occupied with an image or lifestyle, without comprehending what's involved.

The sense of tragedy extends to both families at the end of the movie; the Kims realise that it isn't enough to simply wear the clothes and mimic the lifestyle of those who are richer, whereas the fabric of the Parks' existence is ultimately ruptured from within – in every sense of the word. It's the capitalist structure of day to day existence, seemingly encoded into our very DNA. Ultimately no-one can escape who they are – rich or poor, we are in many ways pre-destined to occupy certain rungs on the social ladder, the poor encircling the rich and vice versa, and fuelling the flames of mania, jealousy and rage. And it's this unwritten rule that has the capacity to destroy us, personal wealth or otherwise healthy family dynamics be damned.

At the risk of being glib, society itself is the parasitic entity, something we all feel underneath our skin. The question is: how far would we go to try and change our pre-defined social status? And is it wise to even attempt such a move? Of course, this only applies to the trajectory of the Kims, who are in a position to attempt to rise above their station. The chilling thing about Parasite as a movie is how plausible it seems; for all of Bong's expertly unpredictable mixing of genres, the movie never feels fantastical or far-fetched.

As much as anything, this owes itself to the superbly believable performances, in particular, the actors playing the power-hungry Kims; deserved winners of the Screen Actors Guild Award for Best Ensemble, they subtly and deftly sketch out the feel of a family whose various crimes and misdemeanours bind them together. The Parks are excellent at what they do, and it's implied in the movie that they've been excellent at it for quite some time. And as much as we're appalled at their actions, not to mention amused at their audaciousness, it's difficult not to feel sad for them come the end.

There's also a wonderful, Dostoyevsky-esque doubling effect in the scene where the Kims first become aware of the existence of Geun-sae. For the first time, this family of tricksters are presented with a horrible mirror of their own reality in the crazed form of Geun-sae, a man who has practically become invisible in order to survive 21st century society. He's a reflection of the Kims' very own desperation and duplicity, their self-assurance punctured as they realise their con artist schemes are far from unique, or admirable.

Just as he has been compelled to live in a defunct Korean bunker, so too are the Kims reminded of their lowly existence in a dank, claustrophobic apartment, utterly oblivious to those walking around on the street outside. (That the street level is higher than their front room only emphasises the gnawing sense of division.) Like everything else in the movie, Bong does a brilliant job in taking figurative, challenging concepts, and rendering them accessible via precise cinematography and superbly physical performances.

As for the Parks, there is perhaps a slight contradiction in the sense of the 'society as a parasite' analogy. Assuming that the family wasn't born into luxury (the movie is hazy, perhaps intentionally so, on how they became rich in the first place), it would appear that the Parks haven't been molded by circumstance – instead, they've taken their destiny into their own hands. Is it, therefore, right to think that the Kims are overreaching themselves? After all, if the Parks made themselves rich, it could potentially work for the Kims? To swing the needle the other way, however, the Parks ultimately face their own destruction come the end of the movie, a sign of how they're also subject to the vagaries and fluctuations of the wider world around them. In the end, the parasite embedded in our very social consciousness has the capacity to infect and corrupt everybody.

Such is the genius of Bong Joon-ho's approach, constantly challenging and disrupting our sympathies right up until the last shot. The essence of a steadily unravelling class system is writ large in the language of the movie, including the lush and arresting score from Jung Jae-il, which begins in a composed, coherent, classical manner, and eventually descends into a more erratic tone, fluctuating in the manner of the characters' emotions. And yet at the same time, Bong isn't interested in delivering a moralistic sermon about man's inhumanity to man; perhaps the real reason why Parasite has resonated so much is that it's huge fun, with bigger, more consistent laughs than most recent comedies, and enough twists to make M. Night Shyamalan blush.

It's a pleasure to be in the company of a movie that's witty and intelligent, but also intent on giving the audience a good time. Throughout Parasite, we're constantly being reminded that we're our own worst enemies, but the meat of the story only truly becomes apparent once the credits play in front of a breathless, giddy audience.

Can't wait to see the movie again? Then click here to book your tickets for Parasite, and tweet us your thoughts on the ending @Cineworld.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)